Historical Background of Indian Constitution

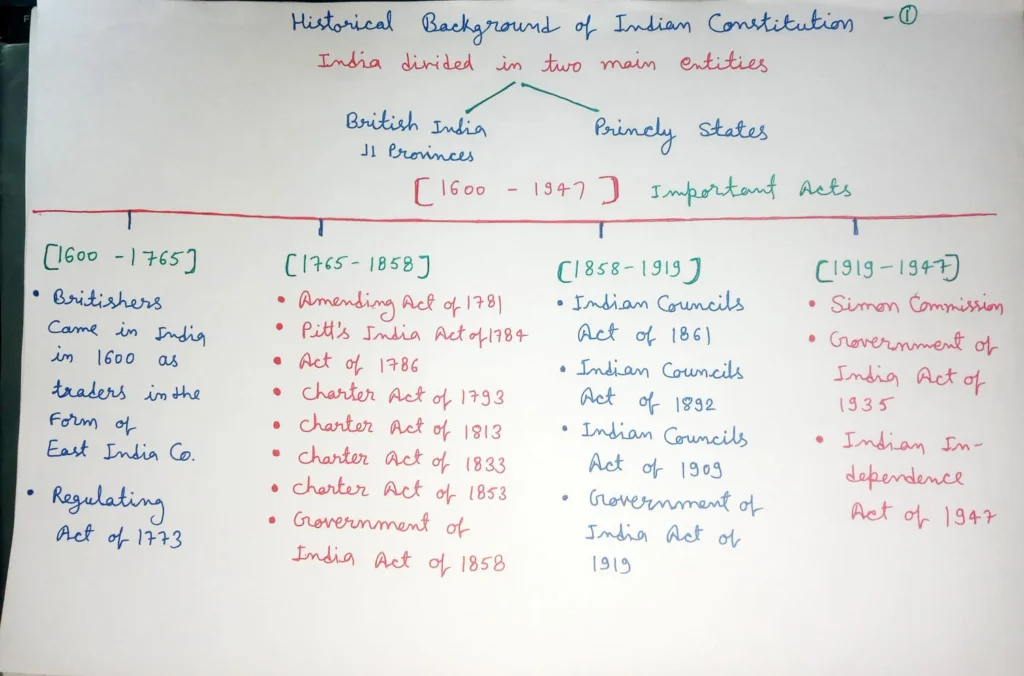

India was divided into two main entities before 1947. The British India which included of 11 provinces and the Princely states ruled by Indian princes under auxiliary alliance policy. In the form of the Indian Union the two entities merged together but many of the legacy systems of British India is followed even now. The history of the Indian Constitution and its growth may be related to numerous laws and regulations that were passed before India’s independence.

Indian System on administration

In Old days political institutions were established by Hindus, In Medival period political institutions were established by Muslims But they do not survive in present day. Then British Period started, The British Period began with East India Company in the year of 1600. We can broadly divide the British period as follows:

- 1600 – 1765

- 1765 – 1858

- 1858 – 1919

- 1919 – 1947

- 1947 – 1950

In 1600, Britishers arrived in india as traders under the name of the East India Company. With the approval of the local authorities, this company set up trading hubs and factories throughout India. For legislative authority, the 1726 charter was introduced. The company stopped presenting itself as traders going upward and started dressing like actual kings. Beginning with the establishment of British control, Britishers began interfering with the administration of civil justice and revenue collection. Then, numerous laws and regulations were passed prior to India’s independence.

Regulating Act of 1773

This act had significant constitutional significance because it was the first step the British government took to supervise and govern the East India Company’s business in India; it recognised, the political and administrative responsibilities of the Company; and it established the framework for centralised management to India.

- The Governor of Bengal was given the title “Governor-General of Bengal,” and a four-person Executive Council was established to support him. The first governor general was Lord Warren Hastings.

- The Governor-General’s Executive Council was established (four members)to support him. A separate legislative council did not exist.

- It changed the previous scenario in which the three presidencies were independent of one another, placing the governors of the Bombay and Madras presidencies under the governor-general of Bengal.

- It called for the formation of a Supreme Court in Calcutta (1774) with a chief justice and three additional judges.

- It forbade the Company’s employees from engaging in any form of private business or receiving gifts or bribes from the “natives.”

- By requiring the Company’s Court of Directors to report on its finances, civil affairs, and military affairs in India, it strengthened the British Government’s influence over the Company.

Amending Act of 1781

The British Parliament passed the Amending Act of 1781, commonly known as the Act of Settlement, in an effort to fix the problems with the Regulating Act of 1773.

- The Supreme Court’s jurisdiction over the actions taken by the Governor-General and the Council while they were acting in their official capacities was disclaimed. Similar to that, it also exempted the company’s employees from the Supreme Court’s authority over their official actions.

- It restricted the Supreme Court’s authority over disputes involving taxes and issues related to their collection.

- It said that the Supreme Court will have jurisdiction over every Calcutta resident. It also required the court to apply the defendants’ personal laws; for example, Hindus had to be tried under Hindu law, while Muslims had to be tried under Mohammedan law.

- It specified that instead of going to the Supreme Court, appeals from Provincial Courts could be made to the Governor-General in Council.

- It gave the Governor-General-in-Council the authority to create rules for provincial courts and councils.

Pitt’s India Act of 1784

- It made a distinction between the Company’s commercial and political activities.

- It established a new organisation called the Board of Control to oversee political activities while retaining the Court of Directors to oversee business affairs. As a result, it created a system of dual government.

- It gave the Board of Control the authority to oversee and manage all civil and military government and tax operations in the former British colonies of India.

Thus, The legislation was noteworthy for two reasons: first, the Company’s Indian territories were officially referred to as “British possessions in India” for the first time; and second, the British Government was granted complete authority over the Company’s operations and administration in India.

Act of 1786

Lord Cornwallis was appointed governor-general of Bengal in 1786. In order to accept the position, he made two demands:

- He should have the authority to override his council’s decision in exceptional circumstances.

- He would also serve as commander in chief. As a result, both provisions were made by the Act of 1786.

Charter Act of1793

- All upcoming Governors-General and Governors of Presidency received the same veto authority granted to Lord Cornwallis over his council.

- It increased the Governor-General’s authority and control over the administrations of the Bombay and Madras Presidency governments.

- For an additional twenty years, it extended the Company’s monopoly on trading in India.

- It stated that the Commander-in-Chief could not serve on the Governor-General’s council unless he was appointed to do so.

- It specified that going forward, Indian income will be used to pay the Board of Control members and their employees.

Charter Act of 1813

- It ended the company’s trade monopoly in India, opening up the Indian market to all British traders. However, it maintained the company’s monopoly over commerce in tea and with China.

- It established the British Crown’s supremacy over the company’s territories in india.

- It made it possible for Christian missionaries to visit India and educate people.

- It allowed for the expansion of western education among those living in the British colonies in India.

- It granted permission to Indian local governments to tax on citizens. They could punish the citizens for not paying taxes.

Charter Act of 1833

The act was final step towards centralization in British India

- It transferred all civil and military authority to the Governor-General of Bengal, making him the Governor-General of India. As a result, the act established, for the first time, a government of India with jurisdiction over the entire territory of India possessed by the British. The country of India’s first Governor-General was Lord William Bentick.

- It took away the legislative authority from the governors of Bombay and Madras. For all of British India, the Governor-General of India was given sole legislative authority. Laws made in accordance with the prior acts were referred to as Regulations, while laws enacted in accordance with this act were referred to as Acts.

- The East India Company’s commercial operations came to an end as a result, and it was replaced by an administrative organisation. In accordance with its terms, the Company’s Indian holdings were held by it “in trust for His Majesty, His heirs, and successors.”

- The Charter Act of 1833 made an effort to establish a system of open competition for the hiring of civil servants and declared that Indians should not be prohibited from holding any positions of authority or employment with the Company. But the Court of Directors objected, and this clause was eliminated.

Charter Act of 1853

This was the final Charter Act the British Parliament passed between 1793 and 1853. It was a crucial constitutional turning point.

- For the first time, It divided the legislative and executive responsibilities of Governor-General’s Council. It asked for the addition of six new council members, known as legislative councillors. For the first time, It divided the legislative and executive responsibilities of Governor-General’s Council . It asked for the addition of six new council members, known as legislative councillors. In other words, it established a distinct Council of the Governor-General, later known as the Indian (Central) Legislative Council. This council’s legislative branch operated like a miniature parliament and followed the same rules as the British Parliament. As a result, legislation was for the first time considered as a unique function of the government requiring unique equipment and procedures.

- It developed a system of open recruitment and selection for civil servants. This made the Indians eligible for the civil service that had been promised to them. As a result, in 1854, the Macaulay Committee—also known as the Committee on the Indian Civil Service—was established.

- It increased the Company’s authority and permitted it to keep control over Indian territories in the name of the British Crown. But, unlike the earlier Charters, it made no mention of a certain time frame. This gave the Parliament enough notice that the Company’s rule may be revoked whenever it pleased.

- It brought local representation in the Indian (Central) Legislative Council for the first time. The local (provincial) administrations of Madras, Bombay, Bengal, and Agra each appointed four of the six new legislative members of the Governor General’s council.

Government of India Act of 1858

- After the Revolt of 1857, commonly referred to as the First War of Independence or the “sepoy mutiny,” this important Act was passed. The East India Company was liquidated by the “Act for the Good Government of India,” which also gave the British Crown control over all of India’s territories and financial resources.

- According to its provisions, Her Majesty’s government would now be in charge of India and would do so in her name. It transferred the title of the Indian Governor-General to Viceroy of India. Viceroy served as the British Crown’s official representative in India. As a result, Lord Canning was appointed as India’s first Viceroy.

- By eliminating the Board of Control and Court of Directors, it put an end to the dual system of government.

- It established a brand-new position, the Secretary of State for India, endowed with total power and management over Indian administration. As a member of the British Cabinet, the secretary of state was ultimately answerable to the British Parliament.

- A 15-member council of India was created to support the Secretary of State for India. The council acted as a consultative body. The chairman of the council was appointed to be the secretary of state.

- It established the Secretary of State-in-Council as a legal entity with the ability to bring and receive legal proceedings in both England and India. “The Act of 1858, however, was largely restricted to the improvement of the administrative apparatus by which the Indian Government was to be supervised and controlled in England.” The Indian government’s system of governance was not significantly changed by it.

Indian Councils Act of 1861

The British government felt it was necessary to seek the help of the Indians in the management of their nation after the great rebellion of 1857. The British Parliament passed three acts in 1861, 1892, and 1909 to implement this plan of association. An major turning point in India’s political and constitutional history is the Indian Councils Act of 1861.

- By involving Indians in the legislative process, it established the foundation for representative institutions. As a result, it stipulated that the Viceroy might name a few Indians to his larger council as unofficial members. The Raja of Benaras, the Maharaja of Patiala, and Sir Dinkar Rao were three Indians Lord Canning, the viceroy at the time, chose for his legislative council in 1862.

- By giving the Bombay and Madras Presidency’s back their legislative authority, it started the decentralisation process. Thus, it reversed around the centralising trend that began with the Regulating Act of 1773 and culminated with the Charter Act of 1833. In 1937, the provinces were granted practically total internal autonomy as a result of this legislative devolution scheme.

- It also authorised the creation of new legislative councils for Punjab, Bengal, and the North-Western Provinces, which were created in 1862, 1886, and 1897, respectively.

- It gave the Viceroy the authority to make rules and orders to facilitate the business transaction in the council. Additionally, it recognised “portfolio” system instituted by the Lord Canning- from 1859. As a result, a Viceroy’s council member was given control over one or more government departments and given the authority to make final decisions on behalf of council about matters pertaining to his department.

- During an emergency, it gave the Viceroy the authority to pass ordinances without the approval of legislative council . The life of such an ordinance was six months.

Indian Councils Act of 1892

- The official majority was still present in the Central and provincial legislative councils, despite an increase in the number of additional (non-official) members.

- It expanded the duties of legislative councils and provided them the authority to criticise the government and review the budget.

- It stipulated that the viceroy, on the advice of the provincial legislative councils and the Bengal Chamber of Commerce, would nominate some non-official members to the Central Legislative Council, and that the governors, on the advice of district boards, municipalities, universities, trade associations, zamin-dars, and chambers, would nominate non-official members to the provincial legislative councils.

Indian Councils Act of 1909

- The act is also known as the Morley-Minto Reforms since at the time Lord Morley served as India’s Secretary of State and Lord Minto as Viceroy.The size of the Central and Provincial Legislative Councils was significantly enlarged. The Central Legislative Council has increased from 16 to 60 members. The provincial legislative councils had varying numbers of members.

- While allowing the provincial legislative councils to have an unofficial majority, it kept the official majority in the Central Legislative Council.

- It expanded the deliberative duties of the legislative councils at both levels. Members could, for instance, ask further questions or introduce budget resolutions.

- For the first time, it allowed for Indians to be a part of the Viceroy’s and Governors’ executive councils. The first Indian to join the Viceroy’s executive council was Satyendra Prasad Sinha. He was selected to serve as the law member.

- By embracing the idea of a “separate electorate,” it established a system of communal representation for Muslims. According to this, only Muslims voters could elect the Muslim members. As a result, the Act “legalised communalism,” and Lord Minto became regarded as the Father of the Communal Electorate.

- It also allowed for the distinct representation of zamindars, universities, presidency corporations and chambers of commerce.

Government of India Act of 1919

The British government first stated on August 20, 1917, that the gradual establishment of responsible government in India was its goal. Thus, the Government of India Act of 1919 was passed and took effect in 1921. The act is also known as the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms after Lord Chelmsford, the Viceroy of India, and Montagu, the Secretary of State for India.

- By defining and separating the central and provincial subjects, it loosened the central government’s control on the provinces. The national and provincial legislatures were given the power to enact laws related to the corresponding lists of topics. However, the system of administration remained centralised and unitary.

- The provincial subjects were further separated into two categories: transferred and reserved. The Governor was to oversee the transferred subjects with the assistance of Ministers answerable to the legislative council. On the other hand, the governor and his executive council were in charge of the restricted topics and weren’t answerable to the legislative council. The term “dyarchy,” which is derived from the Greek word diarche, which meaning “double rule,” was used to describe this dual system of government. This endeavour, however, was mainly a failure.

- It established bicameralism and direct elections for the first time in the nation. As a result, a bicameral legislature made up of a Lower House (Legislative Assembly) and an Upper House (Council of State) took the place of the Indian Legislative Council. Direct elections were used to elect the majority of members of both Houses.

- In addition to the Commander-in-Chief, three of the six members of the Viceroy’s executive Council had to be Indian.

- By establishing distinct electorates for Sikhs, Indian Christians, Anglo-Indians, and Europeans, it expanded the idea of communal representation.

- It awarded franchise to a select group of individuals based on their property, tax, or educational status.

- It established a new High Commission for India in London and gave him some of the duties that had previously been carried out by the Secretary of State for India.

- It authorised the establishment of a public service commission. Consequently, a Central Public Service Commission was established in 1926 for hiring of civil servants.

- It enabled the province legislatures to pass their own budgets for the first time, separating them from the Central budget.

- After ten years of it being in effect, it called for the creation of a statutory commission to investigate and make a report on its operation.

Simon Commission

The British Government announced the establishment of a seven-member statutory committee to report on the state of India under its new Constitution in November 1927 (i.e., two years before schedule). Sir John Simon would serve as the commission’s chairman. Since the commission’s members were entirely British, it was disregarded by all sides. In its 1930 report, the panel made several recommendations, including the elimination of duarchy, the expansion of responsible government into the provinces, the establishment of a federation of British India and princely states, the continuation of communal voting, and more. The British Government organised three round table talks with members of the British Government, British India, and Indian princely kingdoms to discuss the commission’s recommendations.

A “White Paper on Constitutional Reforms” was drafted based on these conversations and presented to the Joint Select Committee of the British Parliament for review. In the next Government of India Act of 1935, the committee’s recommendations were adopted (with some modifications).

Government of India Act of 1935

The Act represented a second step towards an entirely accountable government in India. It was a large document with 10 Schedules and 321 Sections.

- It called for the creation of an All-India Federation with princely states and provinces acting as its units. Three lists—the Federal List (for the Centre, with 59 items), the Provincial List (for provinces, with 54 items), and the Concurrent List (for both, with 36 items)—were used in the Act to divide the powers between the Centre and units. The Viceroy received residual authority. However, because the princely states refused to participate, the federation was never established.

- It ended the provinces’ dyarchy and replaced it with “provincial autonomy.” The provinces were permitted to function as independent administrative entities within their predetermined areas. Additionally, the Act established responsible governments in the provinces, which meant that the Governor had to make decisions based on the counsel of ministers who answered to the provincial legislature. This was implemented in 1937 and abandoned in 1939.

- It allowed for the Centre to adopt a dyarchical system. As a result, reserved subjects and transferred topics were created from the federal subjects. However, this Act’s provision never actually went into effect.

- It introduced bicameralism in six out of eleven provinces. Thus, the legislatures of Bengal, Bombay, Madras, Bihar, Assam and the United Provinces were made bicameral consisting of a legislative council (upper house) and a legislative assembly (lower house). However, many restrictions were placed on them.

- It further extended the principle of communal representation by providing separate electorates for depressed classes (Scheduled Castes), women and labour (workers).

- It abolished the Council of India, established by the Government of India Act of 1858. The secretary of state for India was provided with a team of advisors.

- It expanded the franchise. The vote was accurate for about 10% of the overall population.

- It proposed the establishment of a Reserve Bank of India to manage the nation’s currency and credit.

- It enabled the establishment of joint public service commissions for two or more provinces as well as provincial public service commissions in addition to the federal public service commission.

- It stipulated the creation of a Federal Court, which was established in 1937.

Indian Independence Act of 1947

British Prime Minister Clement Atlee announced on February 20, 1947, that British rule in India would end by June 30, 1948, and that responsibility would thereafter be given to suitable Indian hands. The Muslim League started agitating after this pronouncement, calling for the country to be divided. The British Government reiterated on June 3, 1947, that any constitution drafted by the Constituent Assembly of India (established in 1946) cannot be applied to those regions of the nation that refused to recognise it. The partition proposal, also known as the Mountbatten proposal, was presented on the same day (June 3, 1947) by Lord Mountbatten, the Viceroy of India. The Muslim League and the Congress both approved of the plan.

- By declaring India an independent and sovereign state on August 15, 1947, the British rule over the country came to an end.

- It included provisions for the division of India and the establishment of two autonomous Pakistani and Indian dominions with the option to leave the British Commonwealth.

- It eliminated the Viceroy’s position and established a governor-general for each dominion, who would be chosen by the British King on the advice of the cabinet of the respective dominion. The Indian Government was not to be subject to any obligations from His Majesty’s Government in Britain or Pakistan.

- The Independence act itself might be repealed, and the Constituent Assemblies of the two dominions were given the authority to frame and adopt any constitution for their separate countries.

- It granted both dominions’ Constituent Assemblies the authority to pass laws for their respective regions until new constitutions were drafted and came into force. After August 15, 1947, no Act of the British Parliament could apply to either of the new dominions unless the legislation was specifically extended to those territories by the dominion’s legislature.

- It abolished the position of Secretary of State for India and transferred to the Secretary of State for Commonwealth Affairs responsibility for its duties.

- It announced the termination of British supremacy over the Indian princely kingdoms including treaty connections with tribal territories from August 15, 1947.

- It granted the Indian princely kingdoms the option to join with the dominion of India or Pakistan or to remain independent.

- It stipulated that, until new constitutions were drafted, each dominion and each province would be governed by the Government of India Act of 1935. However, it was permitted for the dominions to amend the Act.

- It eliminated the British Monarch’s ability to veto measures or request that certain bills be reserved for his approval. But the Governor-General had exclusive use of this power. Any law would be subject to the full authority of the Governor-General’s assent on behalf of His Majesty.

- It identified the provincial governors as constitutional (nominal) heads of the provinces, along with the Governor-General of India. They have to follow the guidance of their own council of ministers in everything.

- It removed the title of Emperor of India from the King of England’s royal titles.

- It ended the secretary of state for India’s authority to appoint people to civil service positions and reserve positions. The civil service employees hired before August 15, 1947, would continue to be eligible for all benefits up until that period.

The two new independent Dominions of India and Pakistan took up authority at the stroke of midnight on August 14–15, 1947, ending British rule. The new Dominion of India’s first governor general was named as Lord Mountbatten. Jawaharlal Nehru was sworn in as India’s first independent prime minister. The 1946-established Indian Constituent Assembly evolved into the Indian Dominion’s Parliament.